There is not much to see of the former railway station, but there’s more than there was in 2005. After the station had been closed and the rails pulled up, there remained only two finials from the building, in the grounds of Royd Mount Middle School, and the overgrown railway entrance. Royd Mount Middle School had been built on the site of the station. After the abolition of middle schools and the need for a larger primary school, the school became Thornton Primary School.

The entrance in 2005. ©Photo copyright held by Chris Armour. Photo reproduced by kind permission of Disused Stations.

Since the above photograph was taken, volunteers of Thornton in Bloom, plus the late Councillor Valerie Binney, and local residents removed 50+ years of weeds and detritus from the railway station entrance. Local councillors agreed to spend some of the £30,000 allocated to each electoral ward from the sale of the Leeds Bradford Airport, to ensure seats, flower beds, litter bins, and the two finials replaced the weeds of former years. A local resident, Margaret Sutcliffe, donated an information board about the railway, in memory of her brother James Allen Sutcliffe. Since then Thornton Primary School have re-opened the wall to make an alternative pedestrian entrance to the school.

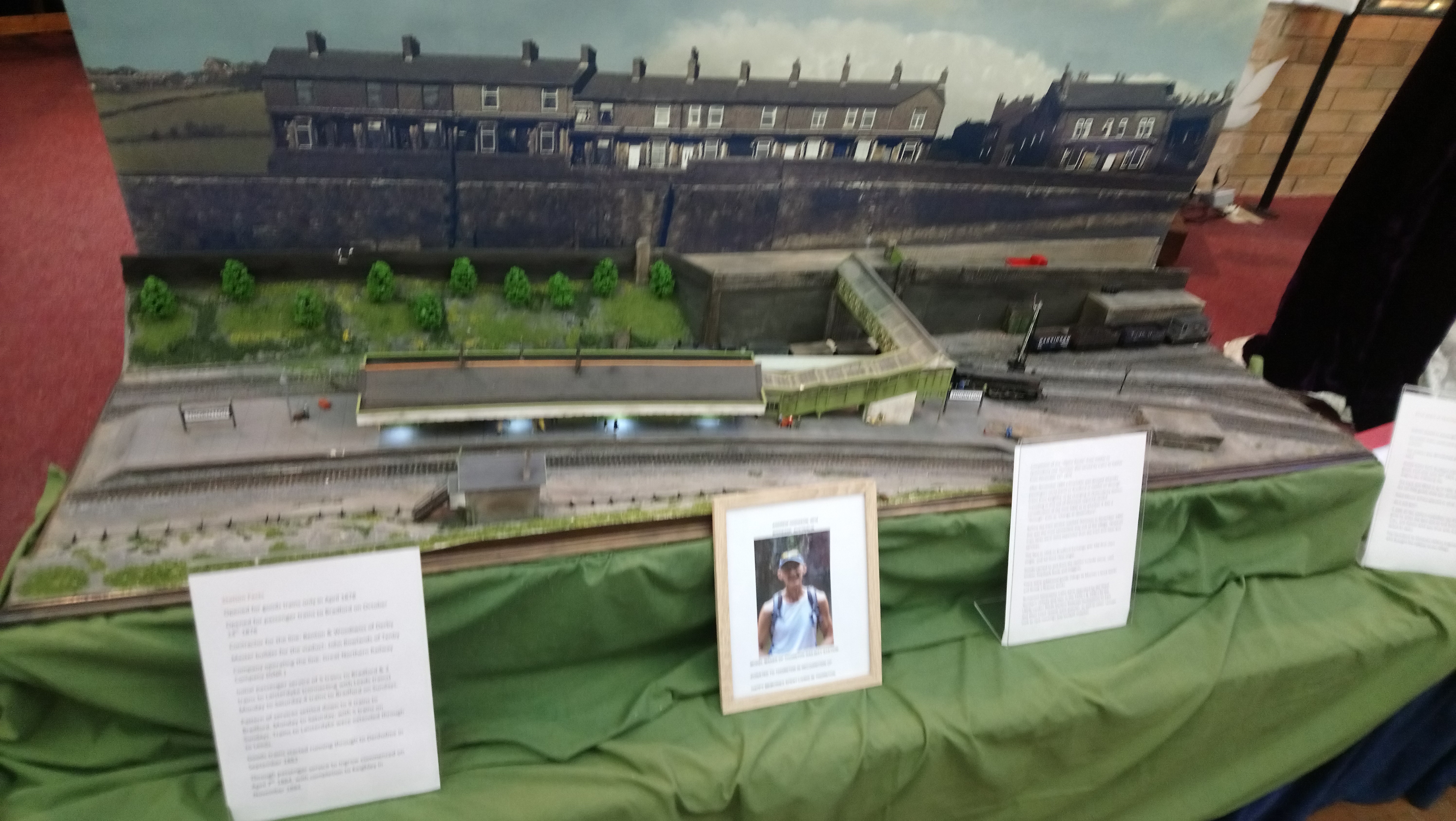

We know what the station looked like from a scale model made by a former Thornton resident, who has since emigrated to Queensland, Australia. It was donated to Thornton Antiquarian Society who paid for it to be brought back to Thornton.

A 50 foot long pedestrian iron bridge went over to the railway “island” platform. (The photograph was not taken for the purpose of putting it on this website). The iron bridge went from the entrance to the station to an island platform, not as shown on the model, but from Thornton Road.

The concrete station name-board has been preserved in the Bradford Industrial Museum.

Thornton had a busy passenger service, but was more used for its goods facilities. It has a stone warehouse measuring 130 ft by 50 ft and handled coal, wood, livestock, maggots, and animal feeds.

A bit of its history

Bradford and Thornton Railway

The Bradford and Thornton Railway Company was formed in the 1860s with a plan to build a railway between Bradford and Thornton, and have a separate large goods marshalling yard on the south side of Thornton Road between the City Road junction and Brownroyd Street, roughly where the Freeman Grattan Holdings warehouse is now. The Thornton and Bradford Railways Act was passed by Parliament on 24th July 1871, after an earlier Bradford and Thornton Railways Act had been withdrawn. The Bradford and Thornton Railways Company was amalgamated with the Great Northern Railway on the 18 July 1872.

The Leeds Mercury of 11 March 1874 reported that the “first sod” of the Bradford to Thornton line had been turned by Mr. Abraham Briggs Foster, Chairman of the Great Northern Railway, at the New Mill Dam, near Messrs. Smith’s Fieldhead Dyeworks on Thornton Road, on the previous day.

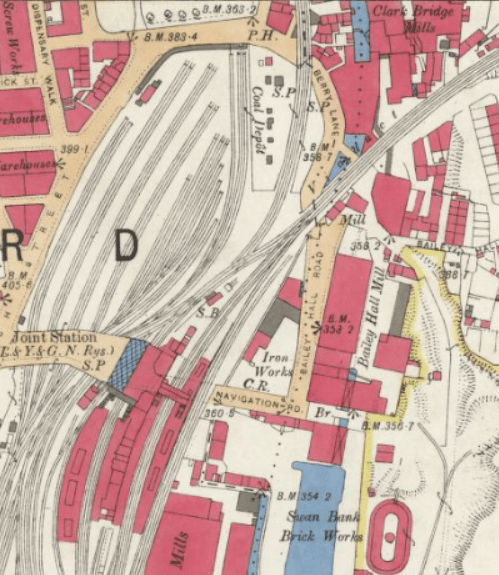

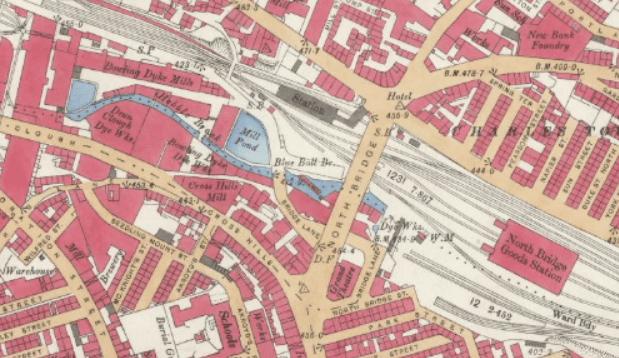

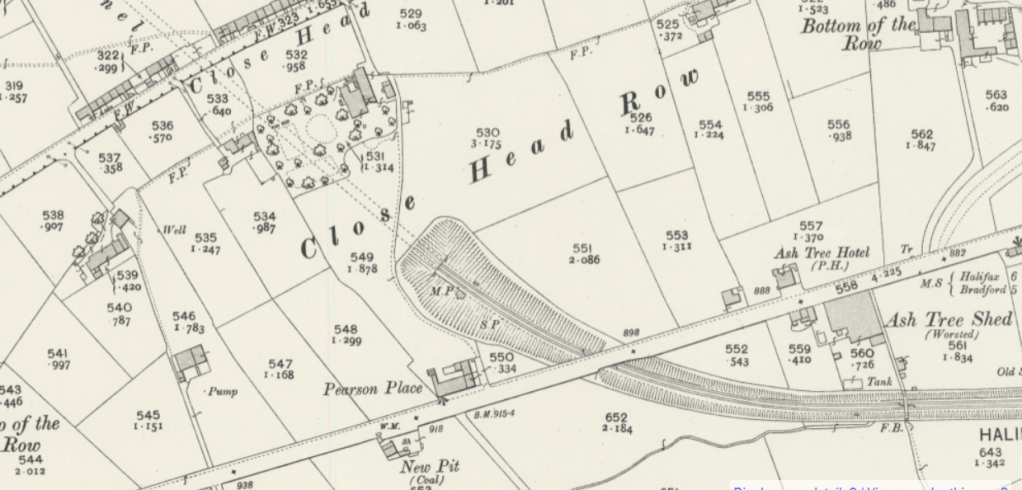

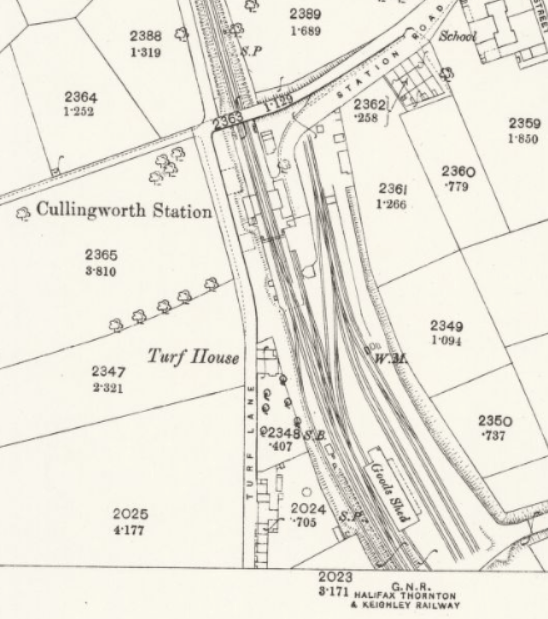

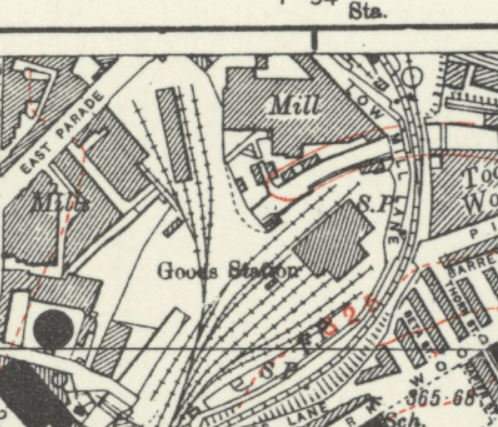

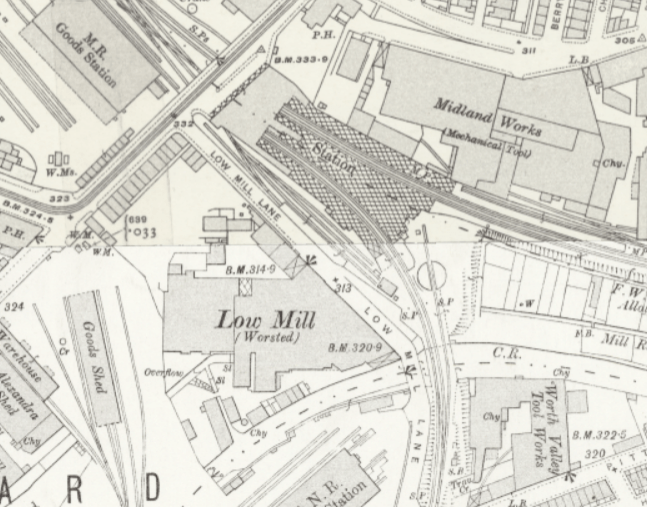

The line ran from Bradford Exchange Station to Thornton Station, via the following stations – (All images of the 1888 Ordnance Survey map are produced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland).

After each description of part of the route, is the relevant extract, in italics, of an article in the Bradford Observer of 5th June 1875 on the building of the railway to that date. starting with the general introduction.

“It is almost four years since the sanction of Parliament was obtained to a bill containing a scheme for the construction of a line of railway from Bradford to Thornton. The works in connection with this new railway were let, in the early part of last year, to Messrs Benton and Woodiwiss, of Manchester and Derby. The first sod was turned at the head of the City Road Branch, near the Fieldhead Dyeworks, on the 10th of March, 1874. Since that time the works have been vigorously pushed forward, there being at present 2000 men and above 100 horses at work, besides twenty steam engines of various kinds; in fact, the working plant is a great deal superior to that employed by ordinary railway contractors.

Further details of all stations can be seen on the Disused Stations website. That website gives many more details about disused stations, including photographs and history of each station and railway lines, and cannot be praised too highly for the detailed information. The green links of names of each station link to the Disused Stations website.

Bradford Exchange Station. Bradford Exchange was about 200 yards further towards the centre of Bradford than the current Interchange station, at the junction with Hall Ings and Drake Street, where steps to the station and a wall remain.

“The line is connected with the Great Northern Railway by a double junction at Ripleyville. This portion, 800ft. in length, called the “easterly fork”, has been made, and a girder bridge is being constructed to support the Lancashire and Yorkshire line at this point, under which the “fork” will have to pass. Shortly after passing this line a junction will be effected with the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway in the direction of Low Moor, but this portion has yet to be complete, for two reasons. The contractors have experienced considerable difficulty in obtaining a convenient place at which to deposit the excavated matter from this deep cutting; and some of the land and property owners in the neighbourhood have refused to allow the contractors access to their roads to the workings. In fact, many of these roads which have been opened to the conveyances of the general public have been closed on the approach of the contractors’ cart.“

St. Dunstan’s, which was near to the end of Conway Street, off Mill Lane. It opened on 21 November 1878, and closed to passengers on 15 September 1952, and was then demolished. From St. Dunstans, the railway went under the current Bradford to Halifax railway to –

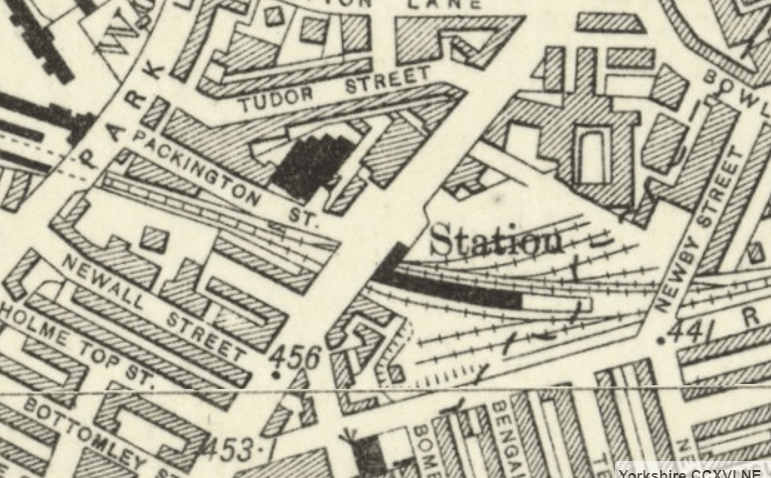

Manchester Road, which was on Manchester Road opposite Pakington Street. It opened on 14 October 1878, and closed to passengers 31 December 1915, and was completely closed on 6 May 1962. The line then went under Manchester Road, near to Pakington Street, then through a cutting, now the site of the Manchester Road Lidl’s, and then in a tunnel under Park Lane and the new part of St. Luke’s Hospital, under Little Horton Lane, to Horton Park Avenue, parallel to the north side of the road. At a point just after it went under Laisteridge Lane the lines to the large City Road Goods Yard branched off to the north west.

“From Park Lane to the Old Lion Inn, in Little Horton Lane, a tunnel is in course of construction, and when finished will run underneath the grounds of the Bradford Workhouse. This tunnel, which will be 311 yards long, is being excavated from both ends. Shortly after commencing work here, a serious obstacle presented itself in the shape of some old coal workings about ten feet below the proposed foundation of the tunnel. Mr. J. Fraser, of Leeds, the chief engineer, however, overcame this difficulty by building up these holes with solid masonry, thus rendering the floor of the tunnel perfectly secure. In order to facilitate the work of excavation, a large steam crane has been erected at the Park Lane end of the tunnel. It is expected that under the most favourable circumstances the tunnel will not be completed until the latter part of next October.

“From the Old Red Lion Inn to Little Horton Park the line has been excavated.

The line from Manchester Road at Packington Street in a tunnel through the Workhouse grounds (now St. Luke’s Hospital new block), under Little Horton Lane, and through a cutting toward Horton Park station. After it runs under Laisteridge Lane the Goods Line branches off towards City Road. see a further map below.

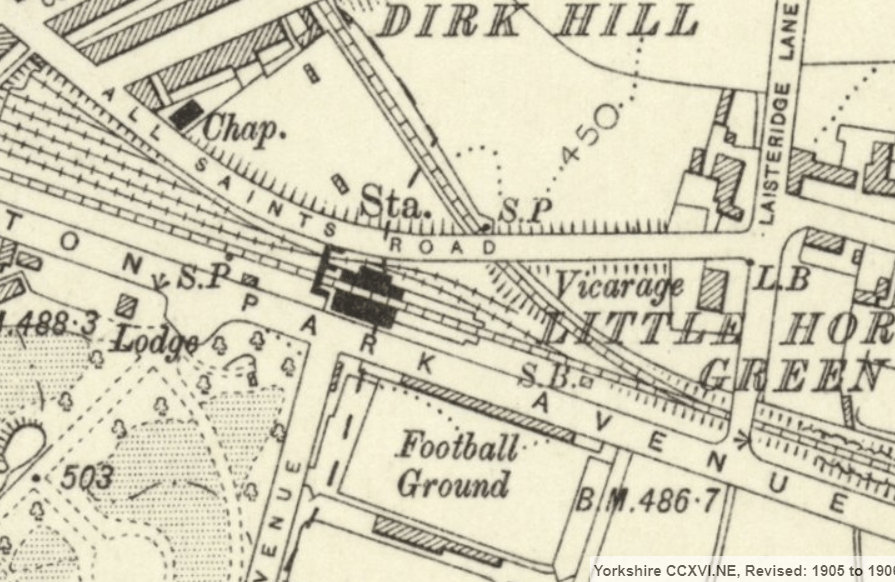

Horton Park, which was opposite the junction with Powell Avenue. It also had access from All Saints Road and there were sidings between All Saints Road and Horton Park Avenue towards the footpath behind Dirkhill Street. It opened on 23 October 1880, closed for passengers as a regular station on 15 September 1952, but opened occasionally after then for football and cricket specials, and closed completely in August 1972. In 2005 the concrete station board could be found in a flower bed of Horton Park on the opposite side of the road. It may still be there. The railway continued on, under Great Horton Road, and then swung south-west over Farnham Road towards Beckside Road to –

“The main line is completed from Horton Park as far as Great Horton Road, near Primrose Hill, with the exception of a small cutting near the contractors’ offices. This cutting, when finished, will carry the line under a bridge which has been constructed beneath the road. Leaving Horton Road, the line, which now turns considerably to the left, has been completed up to where it runs underneath Beckside Lane, excepting a portion of an embankment not far from the Horton Road, where it is proposed to build Great Horton Station. The completion of this embankment and the levelling of the station site will be a comparatively easy matter, as an abundance of “filling” can be obtained from the cuttings near at hand.“

Great Horton, which was at the east junction with Beckside Road, where Ideal Standard used to be, now Storm Trading Group. The station opened on 14 October 1878, closed to passengers on 23 May, 1955, and closed completely on 28 June, 1965. From that station the railway went under Beckside Road, and then through what is now a mixture of employment uses and rough scrub and trees alongside Old Cornmill Lane, to the south of the new Chesapeake Printing works, where it went under Hollingwood Lane to the south of the former Field’s original printing works. The line then went over Pasture Lane and turned left to become parallel to Pasture Lane towards the station at Clayton.

“From Beckside Lane to Hollingwood Lane nothing has yet been done, but at the latter place a bridge is in the course of construction, which will carry the lane over the railway. The road will here be raised about 10 feet, as the level of the line is not that much lower than the present road. Another break in the working occurs until Pasture Lane is reached, where a bridge is being built, under which the road will have to pass. This road will be diverted from its present course, in order to make the approaches to the bridge of an easier gradient.

A little beyond Pasture Lane an embankment 60ft. high is in the course of construction; of which about 400 yards has already been made. Near to the end of this embankment and a little to the right of it is the site of the proposed station for Clayton. The station, when built, will be about 250 or 300 yards distant from Clayton proper; but this will allow of ample room for sidings, etc.”

Clayton, which was situated on an embankment parallel with Pasture Lane and near Station Road, roughly opposite the junction with Thornton View Road. The railway then entered a cutting under Station Road and soon entered a tunnel roughly to the south west of the cul-de-sac end of Bramble Close, coming out south of Fall Top on Brook Lane, close to Queensbury.

“At the end of the embankment the ground rises somewhat abruptly, and a cutting has been made, about 500ft. long, over a portion of which a stone bridge has been erected to convey the road from Clayton to Lane End over the line. About forty yards from this bridge one of the greatest works on the line — the Clayton tunnel – commences. This tunnel, when completed, will be 1044 yards long, 26 feet wide, and 22 feet high, with a uniform gradient of 1 in 55. In order to construct it four shafts were sunk at regular intervals on the hill above, varying from 65 to 142 feet in depth, and a “drift-way” or “heading” 12 feet square from the bottom of the shafts in both directions. Excavations were made from the Clayton end of the tunnel. We learned that last week a connection was made between the shafts (Nos.1 and 2) nearest this end, so that there is now about 500 yards of the “heading“ open, and this is being widened, a small locomotive engine being employed in taking the excavated material away. In no. 3 shaft about 800 yards of this “heading” have been bored, but there is still a distance of 73 yards to be cut before number 2 shaft is reached. In no. 4 shaft, 73½ yards of the “driftway” have been done, and a portion of the arch, or tunnel proper, has been finished near the bottom of the shaft. There is more than eighty yards distance between the heading in this haft and that in No. 3. Altogether there still remain about 190 yards of the heading to be bored. The progress of the tunnel has necessarily been very slow as the strata chiefly consists of strong blue “bind” and “rag stone”, in order to penetrate which blasting has had to be chiefly resorted to. The works have been seriously hindered by the presence of a large quantity of water which has percolated through the fissures in the rock.

The tunnel terminates in a slight cutting near Fall Top, from which the line is carried over Hole Bottom by means of an embankment and a three-arched viaduct about 50ft. high. At this point a two-fork junction will be effected with the Halifax, Thornton and Keighley section.“

Queensbury, which was a bit of a misnomer as the station is about a mile from Queensbury and 400 feet below it, down Station Road, past Queensbury Swimming Baths, then down a footpath to the station, which became triangular, similar to Shipley station, after the Halifax, Thornton and Keighley Railway had been built – see below. It is much nearer to Yews Green than Queensbury. Although the line passed through Queensbury, there was no station there at first; a temporary structure was built, to the east of the later East Junction on 14 April 1879. It had no goods facilities, and was reached only by a primitive and unmade footpath. The start of Station Road at Queensbury is the start of the Queensbury to Thornton Section of the Great Northern Railway Trail. The station opened on 14 April 1879, closed to passengers on 23 May 1955, and totally closed on 11 November 1963. Pre-dating the railway station there was a “tram” cable-line from Hole Bottom Pit to Sharket Head Coal Yard, (off Thornton Road at Queensbury), which transported coal in corves from the pit to Sharket Head. There was a footbridge over this line at the triangular Queensbury Station. Hole Bottom Pit dated from the 1860s. After Queensbury the railway crossed under Cockin Lane, with a siding to Clayton Fire Clay Works, and over Birks embankment. That embankment was 900 feet long, 104 feet high and required 250,00 cubic yards of tipped material. Then under Headley Lane and across Thornton Viaduct to Thornton.

“Between Hole Bottom and Cocking Lane another cutting occurs, a part of which has been already made. At the latter place the lane has been sunk about five feet, in order to avoid a level crossing. Another cutting beyond Cocking Lane, to the right of High Birks, has been completed, and a portion of the Birk Beck embankment, 100 feet high, has been finished. The ground again rises in the neighbourhood of Upper Headley, and here another cutting has been made.

On the other side of this slope, facing Thornton, a large viaduct is in course of construction, which will carry the line over the deep valley through which the Pinch Beck flows. This viaduct, which is the second work in importance on the line, when finished, will be 950 feet long, and will consist of twenty arches, each of 40ft span and 18ft rise. The portion of the viaduct directly over the stream will be 103½ft. high. The same difficulty was experienced here as in the Park Lane Tunnel, viz., the existence of old coal workings about forty feet underneath the foundations of the viaduct. Mr. Fraser in this case used similar means to those which he had employed in the tunnel—the old passages were built up. Unfortunately a fatal accident occurred whilst this was being done. A man was working in one of the passages when the roof gave way, burying him in the earth, in which he was suffocated. The greater number of the piers for the viaduct have already been constructed, but it will be some time before the arches are completed.

Near the Thornton end of this viaduct the station for that place will be erected not far from the Thornton and Denholme Road, at present occupied by the contractors’ offices and the huts in which some of the navvies live. The Bradford and Thornton Railway contract, however, does not terminate here, but at a point about 1100 yards distant, in the direction of Keighley, at the mouth of a tunnel which will be completed when the works for the Keighley section are let. The whole line, from Bradford to Thornton, about 6¼ mile in length, is one continuous rise, in gradients varying from 1 in 196 to 1 in 50. The actual difference in elevation between the two towns is 485¼ft., Bradford being about 385ft, above the level of the sea and Thornton about 870¼ft. The amount of the contract for this line amounts to a little under £300,000, and the works comprise the construction of thirty-nine bridges (including viaducts), 1,000,000 cubic yards of excavation, and 105,000 cubic yards of masonry, besides the making of several culverts, fencing, etc.“

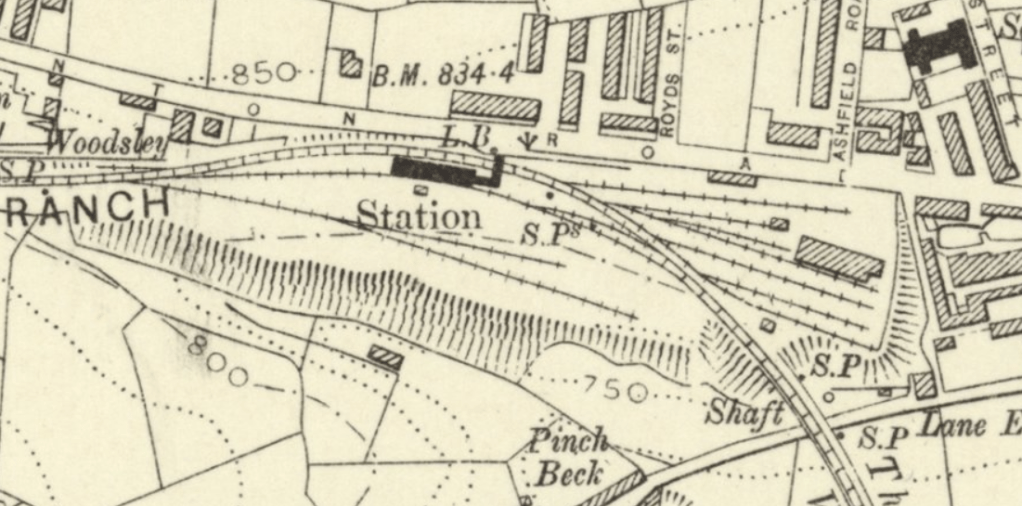

Thornton which had a large goods yard, was built on another large man-made embankment. It opened for freight on 1st May 1878, and for passengers on 14th October 1878. It closed to passengers on 23 May 1955, and the line closed completely on 28 June 1965. A special diesel train of railway enthusiasts stopped at Thornton in 1965.

There is a very good video produced by Forgotten Relics Rambles: Thornton to Queensbury, which includes copyrighted photos of Thornton Station, Viaduct and line, as well as details about the building of the railway.

The Bradford and Thornton Railway began for Goods traffic at the Adolphus Street station, and for passengers, originally at St. Dunstans, but after a short time at The City Road Goods station.

“From the Old Red Lion Inn to Little Horton Park the line has been excavated. At this place the City Road branch diverges to the right, and is carried underneath Horton Road, opposite Summerseat Place, by means of a short tunnel130 feet long, which also runs under the site of Alexandra Villas, one block of which it has been necessary to take down. Running forward in an almost direct line, the railway passes under Legrams Lane. After leaving this road the line begins to turn to the right, and is carried over the Bradford Beck a little to the west of the Fieldhead Dyeworks. At this place an immense culvert has been constructed, 550ft. long, 18ft wide, and 20ft. high, through which the beck runs. The line runs over the site of the New Millers’ Dam, which has been filled up, while a portion of the adjoining land has been levelled, in order to prepare a site for the Thornton Road railway station. About 300,000 cubic yards of earth have been emptied into the old dam, which has been superseded by the construction of the Brownroyd reservoir, a little higher up the valley. The line terminates at the junction of Preston Street with Thornton Road. The length of this branch is about 1¼ miles. And it is now completed with the exception of laying of the permanent way. It is crossed in its course by seven bridges.”

A YouTube presentation of linked photographs with captions, by John Mellor starts with tracing the City Road Goods Yard, and what remains of it exist, and then traces the goods yard line back to just beyond Horton Park Station and then the main Bradford to Thornton line from the start of Horton Park Avenue close to the newer part of St. Luke’s Hospital to Thornton. It is well worth watching

The initial passenger service was five trains each weekday from Bradford Exchange to Thornton and two from Laisterdyke, giving Leeds connections. The opening of St Dunstan’s station in January 1879 meant that Leeds connections were available there, and the Laisterdyke trains were soon taken off, while the Bradford service was increased.

Once out of Bradford, the line was mostly rural and necessitated the construction of many earthworks, viaducts and tunnels. Its hilly nature earned it the nicknames of ‘the Alpine route’ or ‘the switchback’ from its loyal drivers.

The Great Northern Engineer for building the line was Mr. John Fraser.

The Halifax to Queensbury Section

The line started in Halifax, on separate platforms to those existing, as shown in the 1894 Ordnance Survey map, (produced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland, for non-commercial uses).

There were 3 platforms at Halifax Station, over some in the area now used by Eureka! the National Children’s Museum. The line towards Queensbury is that which goes to the east of the coal depot, and over Berry Lane to its next station at North Bridge. There was another line, a high level line, which ran from Halifax St.Paul’s Station to Pellon, through Wheatley Tunnel and on to Holmfield junction.

Further details of that line can be seen on the Disused Stations website. That website gives many more details about disused stations, including photographs and history of each station and railway lines, and cannot be praised too highly for the detailed information.

The next stop was North Bridge. It opened on 25 March 1880, closed to passengers on 23 May 1955, and closed permanently in 1974. Although goods facilities at North Bridge station ceased in 1960 with the closure of the High Level branch to St. Pauls, the goods yard and coal depot were the last part of the entire line to be closed in 1974 when the site was cleared for a supermarket, car park and leisure centre.

The line then went into a tunnel north of, and for the length, of Dean Clough Mills, and then ran between Old Lane Dyeworks and Lee Bank, before entering another tunnel coming out between Ovenden Road and Old Lane. The line continued north under Broad Tree Road to Ovenden Station, alongside Old Lane. The station opened on 2 June 1881, and closed both to passengers and permanently on 23 May 1955.

The Disused Stations site has a great deal of information about this station with photographs. It states that the station building on the former Halifax platform survived as the office and stores as a scrap yard. The buildings were made of wood as passenger expectations were not great, and the wooden building is the only building to survive on the Halifax to Keighley line, as all the stone buildings have been demolished. The station building can be seen on a YouTube video called GNR Halifax – Queensbury – Keighley‘ from 8 minutes 52 seconds to 9 minutes and 49 seconds. After Ovenden the line continued northwards under Old Lane close to its junction with Ovenden Road, under Churn Milk Lane at the Shay Lane end, to where it met the high level railway from Halifax St. Pauls at Holmfield Junction, and north of that to Holmfield Station, which was accessed by a road opposite Beechwood Avenue. You’ll see from the map that the road layout in the 1890s was different from how it is today. Today where Little Moor was Shay Lane, goes northwards in front of Trinity Academy to join Holdsworth Road again

Holmfield station was opened on 15 December 1879. It closed to passengers on 23 May 1955, and closed completely on 27 June 1960.

The line went northwards and veered north-eastwards where the navvies and engineers faced the gargantuan task of extending the line to the Queensbury Triangle. through a 2,501 yards tunnel (nearly 2,287 metres). The construction of the railway to Queensbury is described in several newspaper articles which can be read on the Queensbury Tunnel Society website. There’s also very well-researched Facebook page on the Queensbury Lines

The line from Bradford to Thornton via Queensbury was opened as a joint venture between the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway and the Great Northern Railway between 1874 and 1878.

Thornton to Keighley

The descriptions in italics are appropriate parts of an article in the Leeds Mercury of 24 May 1882 describing the line.

The work of constructing the Keighley, Bradford, and Halifax branch of this railway has now been in operation for several years. That part of the railway most affecting Keighley was commenced in the year 1878, when the first sod was cut at Cullingworth by Mr. Bicknell, the managing partner of Messrs. Beaumont and Bicknell, who had the contract for boring the several tunnels with their now world-famed boring machines.

The works have not progressed very rapidly, probably owing to the to many unforeseen difficulties which have arisen and the hilly nature of the country through which the line passes. In no part will the line be level. When the line is completed, it will be a valuable connecting link between south-west Lancashire and south-east Yorkshire. Not only will it afford to a large population in a district at present almost inaccessible the boon of cheap and rapid communication with the towns of Bradford, Halifax, and Keighley, but as opening to Halifax, Huddersfield, and Wakefield a means of access to Scotland and the north of England by the Midland system. These advantages are not all, for as the town of Keighley shortly expected to be incorporated, the trading and carrying facilities between Keighley and the towns mentioned will be greatly increased. Another important railway scheme is also on foot, namely, the proposed construction of a line from Crossroads, near Keighley, to north-east Lancashire. Should this scheme be carried out, the railway communication with Leeds, Bradford, Keighley, Lancashire, and the north of England would be almost perfect.

Hitherto the inhabitants along the line of railway now being constructed have been placed at considerable disadvantage, owing to the distance they resided from any station, and the manufacturers of Denholme, is Cullingworth, and Wilsden have felt the inconvenience very much. The route of the line is very circuitous, caused by the company touching the villages referred to. Owing to the rugged nature of the country through which the line passes, the carrying out of the works up to the present has involved great expenditure of labour, thus increasing the cost.

Our readers are aware that the line is open from Bradford to Thornton, and after leaving the latter place it passes through Well Head tunnel, which has just been completed, and a perfect line of rails is laid through it. This tunnel is nearly level. Its length is 660 yards. It also forms the summit of the whole line from Bradford to Keighley, the height being 875 feet above the level of the sea; 344 feet above the level of the Lancashire and Yorkshire Station at Bradford; and 317 feet above the level of Keighley Station

The line was extended to Keighley to open to passengers on 1st January 1884.. although there had been a single track goods line to Denholme in 1882. From Thornton station the Great Northern Trail follows the line to the new development at Woodsley Fold. Then it continued on behind what is now Camomile Court, under Thornton Road to the cutting and tunnel under Well Heads. It came out before Denholme Beck, over which the railway bridge exists, and then entered another short tunnel until it reached Denholme Station.

The station opened on 1st January 1884. It was located at the end of Station Road. It closed to passengers on 23 May 1955 and to goods on 10 April 1961. After closure and demolition of the buildings, the site was a timber merchants with a large warehouse built on the site of the station. That has been demolished and the timber merchants have relocated and the area is now covered with new housing. On the opening of the line a local poet / rhymester / songwriter wrote a song entitled “Halifax, Thornton and Keighley Railway. The original is in the Bodleian Library at Oxford, but the Railway Museum at York have transcribed it and it can be seen in their “Songs from the Age of Steam”. It was sung to the tune of “When we went out a shooting”, but unfortunately that tune has been lost. The song was available to buy at a ½d a sheet. It has 6 verses, the chorus goes:

Cheering, steaming, puffing along

Trains well filled with old and young

Joining in a chorus long

Upon the Denholme railway

The text suggests that the song was written after the Halifax Thornton & Keighley Railway act was passed on 5th August 1873 but before the line opened to Keighley goods depot on 1st April 1884.

From this point the line passes by Stubden reservoir to Denholme, where the station will be erected near to the Doe Park reservoir, and within easy access of the village. Leaving Denholme, the line passes through a deep cutting, which is now being rapidly proceeded with. The station ground at Denholme covers about 8¼ acres, and it will, owing to the rapidly rising industries of the village, be one of the most important of the line. Emerging from this cutting, the line will be carried over an embankment at least 90 feet high. The work of constructing this embankment has just been commenced. It will be a work of no small magnitude. The base will be very extensive. It has necessitated the covering and diversion of the Denholme Beck. The scenery hereabout is extremely picturesque, and affords is it splendid view of ‘the surrounding country. This embankment, it is estimated, will contain over a quarter of a million cubic yards of earthwork.

The next station will be at Wilsden, or within a quarter of a mile of the village; but before reaching it the line crosses the valley immediately below the Manual’s Reservoir. (I think this is a mis-spelling of Manywells Reservoir, which is known as Hewenden Reservoir on maps of the period)

The railway then went on through two short tunnels to a station called Wilsden, but it would have been more honest to call it Harecroft. Almost opposite the Station Hotel in Harecroft is Station Road which led to the Wilsden station.

The station was opened on 1st July 1886, closed to passengers on 23 May 1955, and closed completely on 11 November 1963.

Shortly after leaving Wilsden Station the line crossed Hewenden Viaduct which was the first part of the Great Northern Trail to be opened. Hewenden Viaduct is a Grade 2 listed building. The Great Northern Trail, Wilsden Station to Cullingworth is described and mapped here. The trail starts near to the site of Wilsden Station, goes over Hewenden Viaduct, through a cutting, then across the much shorter Cullingworth Viaduct. After that the trial veers to the right before doing a 90° angle to New School Lane and / or Fieldside and onwards to Halifax Road at Cullingworth. On the north (Cullingworth side of Hewenden Viaduct), next to the Information board is a plaque to the memory of Phil Jackson, a construction worker for Sustrans who was killed in a motorcycle accident at the age of 35.

The information board states “This plaque is dedicated to the memory of Phil Jackson 1974 – 2010

Phil was instrumental in opening the viewing platform and helped construct many miles of cycleways throughout Yorkshire. This was one of his favourite places.”

“The company originally did not intend to cross the valley, but owing to the opposition of the Bradford Corporation, they were compelled to construct a viaduct of great length, known as the Hewenden Viaduct. The Corporation urged if the railway was taken to the south of the Manual’s Reservoir, there would be a danger of “tapping ” the Manual’s springs, which form a valuable source of the Bradford water-supply. Hewenden Viaduct, now in course of construction, is one of the most important features of the line, and is entailing a great amount of labour. The viaduct will consist of nineteen arches, and with one exception, each will have a span of 50ft. The viaduct will, at its extreme height, be 120ft. The foundations are deeply laid. A large number of men are now employed on this part of the works. A considerable quantity of water has been met with, and two engines are at work night and day pumping water from the foundations. The arches are constructed of stone obtained from the adjoining cutting.“

.After the Hewenden Viaduct the line enters an embankment and a cutting and then across the shorter Cullingworth Viaduct, remains of which can still be seen.

“Leaving Hewenden, the line proceeds by way of Cullingworth, and the various cuttings are nearly completed, thus facilitating the disposal of the earth from the Cullingworth cuttings, At Cullingworth the line crosses the main roads from Keighley and Bingley by a viaduct consisting of nine arches, each having a span of 40 feet. The viaduct is nearly completed. Cullingworth station will be a few hundred yards beyond. The site is an admirable one, being very level and close to the village. This will cover about six acres of ground.“

The railway then went to the west of Cullingworth to the station at the west end of Station Road. The station opened to passengers on 7th April 1884, and closed to passengers on 23 May 1955.

(Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland, for non-commercial uses).

After leaving Cullingworth Station the railway goes northerly and then turns to enter the Lees Moor Tunnel in a westerly direction.

Leaving Cullingworth, the line passes through another deep cutting, nearly a quarter of a mile in length. As in other parts, the work has been found to be very heavy, as solid rock was met with within 12 inches of the surface. The stone obtained from this cutting has been used in the erection of bridges, culverts, &c., on the line. This cutting is now rapidly approaching completion, and two engines are at work daily carrying materials for the purpose of forming embankments. It terminates at the south end of Lees Moor tunnel, and a piece of swampy ground will here be crossed by another viaduct.

The Lees Moor tunnel is a work of great magnitude, as for the most part it passes through solid stone. At the Cullingworth end of the tunnel shafts are now being sunk and preparations made for carrying on the work more energetically. Hitherto the tunnelling operations have been carried on from the Keighley side, as the gradient is 1 in 73 falling towards Keighley. The tunnel will be a massive stone construction. The walls are two feet thick. and the height fourteen feet. The work is proceeding at the rate of 70 yards per month, and it is expected that it will be completed within twelve months.

(Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland, for non-commercial uses).

At the Keighley entrance of the tunnel a large amount of extra labour has been entailed by a landslip near the river Worth. This was caused by the making of the embankment, and the great weight of earth upon the clayey ground brought about the slip. To render the embankment safe, trenches varying in length from 20 to to 60 yards have been made to the depth of 14 yards, and refilled with stone. This tunnel brings the line into the valley of the Worth at Crossroads, the proposed terminus of the new line to north-east Lancashire. A small station will be erected here. (never proceeded with).

(Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland, for non-commercial uses).

“The line from this point follows a comparatively straight course to Keighley. Midway between the river Worth and the highway another station will be erected at Ingrow, in close proximity to the Midland station, and about six acres of ground has been reserved for this purpose.

The line will then pass through New England Gardens, and enter the Worth Valley line near to Worthville. The work of construction has up to the present only reached Ingrow. The Midland Railway Company are widening the Worth Valley line from Keighley to Worthville for the purpose of admitting the Great Northern line; and this work, owing to the Haworth, line being a single one, will cost about £24,000.

The site of the Great Northern Station in Keighley has not yet been decided upon, nor is it known whether a joint station will be erected for the use of the Great Northern and Midland Companies; but from the plans it appears that the Great Northern will run into the Midland Station. The goods station, it is thought will be near to Greengate, and open out into Halifax Road – a very central part of the town.

(Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland, for non-commercial uses).

(Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland, for non-commercial uses).

“The total length of the line from Thornton to Keighley is about 6½ miles, and the contractors for the works are Messrs. Benton and Woodiwiss. The engineers are Messrs Fraser and Sons, of Leeds. The company is bound by an Act of Parliament to have the line completed within two years from the present time.

The video GNR Halifax – Queensbury – Keighley‘ is worth watching.

A account of building the railway from Thornton to Keighley from the Leeds Mercury of 14 May 1883

“THE NEW RAILWAY BETWEEN THORNTON AND KEIGHLEY

Nothing is more easy than to overlook difficulties which one has hand no hand in removing. In every branch of art and industry it is the same; the more complete and finished the parts, the less labour seems necessary to put them together. What more natural, for instance, while travelling in a comfortable, fast-going railway carriage, than to imagine the road always smooth and level, the cuttings, and even the tunnels, made almost as readily as a they are passed. In order to grasp some of the difficulties in the way of such a road, a little practical knowledge is needed-as much as may perhaps be picked up in a walk along a half-finished line, even though it be short, like the new link between Thornton and Keighley. Starting from Thornton – a village whose worsted industries bring her into close connection with Bradford – runs a double line of metals. The direction is north-easterly, almost continuous with the main Line from Halifax to Queensbury, and through a district whose uneven surface has offered many an obstacle to the engineer.

Scarcely half a mile from the little station at Thornton these obstacles show themselves in the shape of a shallow cutting that leads with a gentle curve to the foot of Thornton Heights. Passing beneath the highroad to Bradford, between a deeper cutting in sandstone and shale, the line enters Well Head Tunnel. This opening, bored through the solid base of the Heights, is 660 yards long, and being practically straight, demanded no more than ordinary skill and labour in construction. Another steep stretch of cutting, which ends abruptly only to start again a little farther north, and the metals disappear within the walls of a shorter tunnel. Hitherto the road has been permanently laid, and there is nothing attractive along the route. But beyond the sharp bend which the line makes on leaving the tunnel there is a change. Engines dragging after them waggons laden with earth and pieces of stone, and men busy upon the foundations of some building, break the monotony of the scene.

Here, on the right, will stand Denholme Station, its highland platform hiding from view a portion of the Doe Park Reservoir, with its background of dark hills. The village itself just peeps from the top of the grass-covered slope seen on the left, or lies within concealment to the west. A heavy landslip, which took place during the process of cutting, added greatly to the labour hereabouts, and a few yards from the station there are still left a few signs of the nature of the difficulty. The road has not been permanently laid, so that mud, smoke, and general hurry make progress on foot less comfortable. Then comes a tunnel, not very long, opening out to the north between a couple of mud banks, whose treacherous components are more difficult to handle than solid rock. And now for the first time the scenery becomes at all interesting. A hollow appears on the right, with slopes north and east dotted with hardy forest trees. A little beyond, the hollow develops into a long, narrow valley, losing with compactness much of its prettiness. This loss, however, is compensated by the glimpse which the left bank gives of the Hewenden Reservoir – a large sheet of water lying at. the foot of two or three thinly wooded hills. At this point the line crosses what was once a well-timbered combe, watered by a tiny stream. Two hundred and twenty thousand cubic yards of soil quickly blotted out this nook, and raised its depth of ninety-one feet to the level of the rails.

A station for Wilsden was intended to be placed near this embankment, but the project has been abandoned, and for the present at least Wilsden, with its population of nearly 4,000, engaged chiefly in the worsted trade, must be without a railway a station. Visitors who delight in the romantic scenery of Goitstock woods and waterfall will regret this quite as much as the inhabitants themselves. (On 24 July 1885 there was the following report in the Leeds Mercury:

“Hewenden viaduct, 1,000ft. long and 141ft. high, is a little ahead, its a 17 stone arches, each spanning 50ft.,, reaching over pasture lands, and occupation roads. Some of the piers are sunk as far as 6Oft. into a bed of blue clay, shale, and sandstone. All the arches, with one or two exceptions, have been “keyed” that is, have had their keystones fixed, and nearly the entire length of the viaduct may be traversed upon thin boards stretched from girder to girder, in whose multitude, and not in whose individual strength, lies safety. The view here again is pleasant, Away to the right are seen the summits of a treble range of hills; nearer may be traced the Aire valley; and still nearer, a few prettily situated houses, with a mill fed by the embanked stream which now runs from a culvert -sunk 10ft. down into solid sandstone. A wood is on the left, occupied at this moment by men and youths whom the dinner hour has released from work in the busy little colony close at hand. Just now the only accessible way to the line beyond the viaduct is to slide down twenty feet of arch, and to descend a perpendicular ladder to a narrow rail platform suspended a considerable height above the ground. The metals gained, the path is easier, and the view of hill and valley becomes more extensive. until Cullingworth suddenly appears in front.

Cullingworth is a quiet little village, with an old-fashioned air about it that hardly consorts with the fact that its history is not of very ancient date. Like most of their neighbours, the villagers, numbering over 2,000, are employed in the worsted trade, and will doubtless welcome the new railway as a means of stimulating a rather a stagnant business. The station and goods warehouse, which already begin to give signs as to their character, lie a hundred yards past a small viaduct of nine arches over the Bradford and Haworth and the Bingley and Halifax highways. So uneven was the ground in the immediate neighbourhood that 200,000 cubic yards of material had to be excavated before the station embankment could be made.

Further north still the cutting lies between beds of gritty sandstone, upon which men are likely to be fully employed for two or three months. At this point there is a temporary break in the line. The route may, however, be taken up again a few hundred yards beyond by any person who does not mind descending a sort of pit sunk deep into the earth. Descent is made either by a ladder tied to the streaming sides of the pit, or by means of a mud bucket let down a shaft from a more remote embankment. The ladder gives access to the first heading – a low, narrow opening, which few, hearing the constant rumbling as of falling material and rushing water, and feeling the intense darkness, would care to enter far without light or guide. The mud bucket, though very dirty, is a safe conveyance into the tunnel. The eyes grown accustomed to the pitchy blackness, the ears familiar with the hollow rush of sound, and the feet having found a solid base beneath six inches of mud and water, one may look around with some degree of comfort. In the direction of Cullingworth, a few lights moving about will-o’ the-wisp fashion, show where miners dig and delve the earth and stones which the slow-moving trolley brings to the foot of the shaft. This is the first heading or narrow passage into the tunnel proper. By the glare of a naphtha lamp, one may venture north through broad finished parts of the opening, until there comes the necessity to mount a ladder and grope one’s way along a mud-painted platform uncomfortably near the roof. Then another descent to the ground, ankle-deep in water, followed by a creep through some loose scaffolding into a bottle-neck junction, where men working north and men working south meet. Mud, and confusion and darkness are again the distinguishing characteristics. Everything and everybody is in an agony of preparation to remove this second heading, as it is styled, and open out the tunnel into the light beyond. For over 1,500 yards, through the base of a ponderous hill, runs Lees Moor Tunnel, in a gentle curve broken only in the centre. Originally it was intended that the tunnel should be about 1,000 yards long, but an addition of nearly 500 yards has been made in order to shorten the cutting on the Cullingworth side, and thus secure a greater triumph of engineering skill.

Quitting the tunnel, the metals run along an embankment, the right boundary of which is a hill – the site of New Road-side – while the left looks down upon a valley of no particular attractions. To Damens, past the place of a future station at Cross-roads, and across the open arch which spans Woodworth, the despoiled residence of Mr. Robert Clough, is a short journey.

At Damens, the contractors, Messrs. Benton and Woodiwiss, had to contend with a very serious slip. An embankment was being made upon the level when the ground beneath gave way, so that the work had practically to be begun again. Near this point the Valley of the Worth approaches the line on the left, and with an eastward turn the rails join the Worth Valley line at Ingrow.

About three-quarters of a mile ahead is seen the now railway station at Keighley, together with the extensive foundations upon which will rise a Great Northern goods Warehouse. The passenger station is to face the Worth Valley platform, and will therefore be practically under the same roof with the Midland main line for the north. The convenience of such an arrangement needs no demonstration. It is one for which travellers in the district must be grateful, and of which they will doubtless make speedy use. A few months more and the inhabitants of Keighley will be put into possession of a second route to Bradford, and a direct railway connection with Halifax. Hitherto Keighley has had only one railroad connection with the outside world, the Midland line between Skipton and Bradford. By the introduction of the Great Northern Railway, and the not too early addition to passenger and goods accommodation, it is hoped that some permanent benefit will be felt, both in the social and the material condition of the town.”

(Updated 17 February 2024)